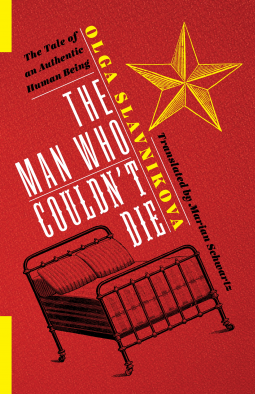

The Man Who Couldn't Die

The Tale of an Authentic Human Being

by Olga Slavnikova

This title was previously available on NetGalley and is now archived.

Send NetGalley books directly to your Kindle or Kindle app

1

To read on a Kindle or Kindle app, please add kindle@netgalley.com as an approved email address to receive files in your Amazon account. Click here for step-by-step instructions.

2

Also find your Kindle email address within your Amazon account, and enter it here.

Pub Date Jan 29 2019 | Archive Date Jun 03 2019

Talking about this book? Use #RussianLibrary #NetGalley. More hashtag tips!

Description

After her stepfather’s stroke, Marina hangs Brezhnev’s portrait on the wall, edits the Pravda articles read to him, and uses her media connections to cobble together entire newscasts of events that never happened. Meanwhile, her mother, Nina Alexandrovna, can barely navigate the bewildering new world outside, especially in comparison to the blunt reality of her uncommunicative husband. As Marina is caught up in a local election campaign that gets out of hand, Nina discovers that her husband is conspiring as well—to kill himself and put an end to the charade. Masterfully translated by Marian Schwartz, The Man Who Couldn’t Die is a darkly playful vision of the lost Soviet past and the madness of the post-Soviet world that uses Russia’s modern history as a backdrop for an inquiry into larger metaphysical questions.

Olga Slavnikova is the author of several award-winning novels, including A Dragonfly Enlarged to the Size of a Dog and 2017, which won the 2006 Russian Booker prize and was translated into English by Marian Schwartz (2010).

Marian Schwartz translates Russian contemporary and classic fiction, including Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, and is the principal translator of Nina Berberova.

Advance Praise

"The Man Who Couldn’t Die is an overlooked masterpiece of post-Soviet prose by one of contemporary Russia’s most important authors. It reveals how Slavnikova’s descriptions (and Schwartz’s English equivalent) belong alongside those of Vladimir Nabokov, Iurii Olesha, and Nikolai Gogol as truly revolutionary in Russian prose."

—Benjamin Sutcliffe, Miami University

Available Editions

| EDITION | Other Format |

| ISBN | 9780231185950 |

| PRICE | $14.95 (USD) |

Featured Reviews

The Man Who Couldn't Die is an interesting piece, but it's probably not going to be one that appeals to all readers. It is a deeply introspective work that considers not only the human psyche and metaphysical conundrums but also modern-era politics. In the latter respect it is a timely work, as it could also be said to represent more recent events in the Western world. I enjoyed the dilemmas the piece posed; however, at times I felt somewhat distanced from the characters. I would have liked to have established a stronger connection with them. Then again, that separation may have been a conscious decision on the part of the author. Either way, this is not an 'easy' or light read, so I would only recommend it to those who like a good dose of heavy introspection and philosophy in their literary fiction.

John L, Reviewer

John L, Reviewer

With the death of the Soviet Union, a loving family have to contrive to keep it alive in their family home, making it look like nothing had changed for their ill elder member, who would be too aggrieved of the change they remain ignorant of. They even have to conspire to make their own TV news, and maintain the drudgery of Communism, while outside their four walls the country bursts into progress, happiness and newfound freedom. That, obviously, is Goodbye Lenin!, but oddly the same situation is evident here, as a WW2 veteran with a stroke remains in bedbound ignorance of Brezhnev's death, and any futuristic alterations in the outside world. The two scenarios are remarkably alike – although I don't think anybody would accuse Russia of bursting into happiness.

What this book does is burst into the oh-so typical modernist style, of over-long, overly-complex sentences, to disguise lack of narrative. There really are swathes of this that could be ignored for the sake of the core story, of what happens when family members get caught up in political things. I found it hard to justify staying with this at times, as I also found it hard to understand the political sides and whose machinations were against whom. The result of it all is that, paradoxically after I bemoaned the lack of story, the end scene felt like too much of a rush to justify it all. This dense, literary read is an acquired taste. One and a half stars – I'll stick with my film, which is easy to say as it's my favourite of all time.

Joseph S, Reviewer

Joseph S, Reviewer

Excellent writing in language and style. The translation seems to keep the original’s detail. It seems almost modernist in the lack of dialog and concentration introspective. There is the acquired taste of Soviet literature in this late novel. It is almost like the isolation and sudden freedom in life is reflected in literature.

Thank you NetGalley and Columbia University Press for this ARC in return for my honest review.

Well, being Russian, I was very optimistic about this book. I am very interested in contemporary Russian literature, and it was a great opportunity to explore translated Slavnikova.

I did not enjoy it as I expected. Russian writers love to create long sentences trying to put everything in and overcomplicating it. I don’t believe it works well in Russian and I think it was terrible in translation. Some sentences last whole paragraph and I was lost when I finally reached the dot. I had to come back and re-read breaking it up in few part to get the sense.

I also felt like there was no real plot and no real character development. I was frustrated reading it, as I didn’t understand what the novel was about and who? Was it poor Marina struggling to find her place under the sun? Was it veteran Kharitonov as synopsis says? Was it about corrupted elections? Was in tumbled Russia in those horrible 90s? There are more questions than answers.

I was pushing myself to finish it in search of at least one answer.

Nope. Nothing.

Librarian 199509

Librarian 199509

I wasn't expecting this to be so much a domestic melodrama. The titular man barely features in the novel and I am still unsure as to why his family felt that they couldn't age the apartment beyond Brezhnev. Something about the book prevented me from really feeling a connection to any of the characters. The story has good details about life in Russia after the fall of the Soviet Union, but the world felt very small. Not bad, but also made the story very slow paced and claustrophobic.