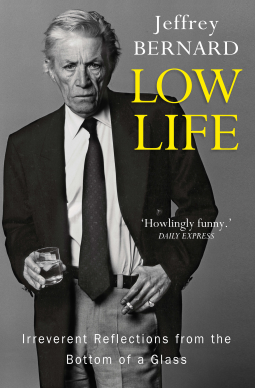

Low Life

Irreverent Reflections from the Bottom of a Glass

by Jeffrey Bernard

This title was previously available on NetGalley and is now archived.

Send NetGalley books directly to your Kindle or Kindle app

1

To read on a Kindle or Kindle app, please add kindle@netgalley.com as an approved email address to receive files in your Amazon account. Click here for step-by-step instructions.

2

Also find your Kindle email address within your Amazon account, and enter it here.

Pub Date Nov 28 2019 | Archive Date Dec 16 2019

Duckworth Books | Duckworth

Talking about this book? Use #LowLife #NetGalley. More hashtag tips!

Description

Described as the Tony Hancock of journalism, Jeffrey Bernard wrote only about himself and the failures of his life – with women, drink, doctors, horses – which have become legendary.

Antiauthoritarian, grumpy, charming, politically incorrect, funny, drunk and always mischievous, Bernard could usually be found at the Coach and Horses pub on London’s Greek street, a lit cigarette in his mouth and a drink in hand. He was joined by famous friends including Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, Graham Green, Peter O’Toole, Ian Fleming and many others and their conversations – as well as with whomever was tending bar at the time – served as the basis for his writing.

Low Life is an irresistible collection of the best of Bernard's celebrated autobiographical contributions to The Spectator, once described as 'a suicide note in weekly instalments'. Previously published in two volumes entitled Low Life: A Kind of Autobiography and Reach for the Ground, these books are now available in a single volume containing all his derisive reflections on life.

Available Editions

| EDITION | Paperback |

| ISBN | 9780715653593 |

| PRICE | $9.99 (USD) |

Links

Featured Reviews

Greville W, Reviewer

Greville W, Reviewer

Wow, this brought back some memories. I used to read Jeffrey Bernard’s Low Life column regularly in The Spectator magazine throughout the 80s and I’d forgotten how well written and anarchic they were.

Of course his uttering are dated and in many cases totally politically incorrect when read now but they hark back to a time when Soho and Covent Garden was full of so-called characters and was louche and vibrant rather than the homogeneous area that it is now.

Those days are gone now but it’s good to be reminded about them now and again.

A nostalgic and at times hilarious read.

Sid N, Reviewer

Sid N, Reviewer

Jeffrey Bernard’s writings are by turns hilarious, acerbic, self-excoriating, bitter and very sad. I had read only a little of him before now and I’m very glad to have a chance to read more, but it’s a mixed experience for me.

This is a collection of Bernard’s weekly columns for the Spectator which he wrote for about twenty years from 1975 almost until his death from the effects of alcohol abuse. Many of them recount anecdotes of his chaotic life and of the fellow drinkers and other “low life” with whom he associated. The writing is brilliant: it is poised, elegant, witty and (certainly about himself) uncompromisingly frank. There are some genuine laugh-out-loud moments and plenty of amusing ones, but there is also a fundamental bleakness under the devil-may-care facade which, in quantity, became quite hard to take. As one might expect, his attitudes, especially toward women, are anything but enlightened and even making allowances for the prevailing views of the period the sexism and misogyny are pretty repellent at times. Set against this is his refusal to have anything to do with pomposity and pretentiousness, and his skewering of them can be very enjoyable.

This is definitely a book to dip into. I can see the appeal of one of these articles per week (or less, because he was frequently and famously “unwell”); too many together left me feeling a bit desolate and rather soiled. The collection has many redeeming features, including the sheer excellence of the prose, but for me needs to be handled with a little care.

(My thanks to Duckworth Books for an ARC via NetGalley.)

Abby S, Reviewer

Abby S, Reviewer

This was a really entertaining read for me.His columns draw from anything and everything politics his personal life his alcoholism.He can be cranky funny angry moody but always well written,Highly recommend.#netgalley#duckwirthpress.

Cristie U, Book Trade Professional

Cristie U, Book Trade Professional

This was a great read, as I had never heard of Jeffrey Bernard before finding this book. I can see why his column was so popular, as his writing makes him someone that the reader can relate to, whether or not they share the same struggles as him with alcohol. The honesty of his writing in these snippets from his column shows just how much he was struggling despite the success he achieved. I highly recommend this!

David S, Reviewer

David S, Reviewer

Twenty years ago my best friend died from Korsakoff’s syndrome, a little-known form of dementia linked to alcohol, not a death that most people associate with drinking.

Given that I should have really disliked this series of essays, in which drinking forms a contiguous thread throughout.

Painfully honest chronicling Jeffrey Bernard's failing health; humorous with characters from a bygone day, which is its only fault in that many people featured have slipped from modern memories; and elegantly written.

"I don't know of much work more tedious than reviewing a book that one doesn't want to read in the first place, but it is useful work and cannot be turned down."

So he writes in this witty compilation, for this reviewer it was hardly a tedious chore.

This is not really something of which I am proud, but there was a time, in the 1990s, when I was a regular reader of The Spectator magazine. I hasten to add that I was not, at that time or, indeed, at any time, an admirer of the political stance of that magazine and I do hope that I can rely on you all to keep this embarrassing admission to yourselves.

If I remember those distant and, in comparison with today, relatively peaceful and uneventful times correctly, The Spectator, and its readers, were somewhat dissatisfied with John Major’s Conservative government and I must admit that I bought the magazine for the simple pleasure of witnessing, in its pages, the divisions within the government and its supporters. John Major received a lot of criticism, not to say outright mockery, back then, and it amused me greatly, but now I find that, having witnessed the efforts of the three subsequent Conservative Prime Ministers, John Major’s performance in the role is now appearing more statesmanlike as each day passes.

So looking back, this guilty pleasure seems to have been a little cynical, not to say priggish, of me but perhaps it helps to explain the fact that the page of the magazine I was certain to turn to each week was Jeffrey Bernard’s “Low Life” column. Bernard didn’t set out to impress this left of centre, liberal young fellow with his curmudgeonly, politically incorrect columns but the fact is that he wrote so elegantly, and with such dry wit, he could not fail to do so. I was hooked.

Bernard’s column served as a contrast, or counterpoint, to The Spectator’s “High Life” column, written each week by “Taki” who is apparently a wealthy socialite, whatever that is. I can remember nothing of “High Life” at all, probably because I never found it interesting or diverting. But when I picked up this book, a collection of Bernard’s “Low Life” columns, I had a clear memory, even after twenty-five years or so, of the style and panache of his writing if not the actual content of his work.

Apart from the women in his life Bernard appears to have had three great loves: Soho, horse-racing and alcohol and these are the great themes that run through all his columns. The “Low Life” that Bernard wrote about each week was the life of Soho where he had lived for much of his adult life. This is the Soho of The Coach and Horses, The French House pub and the Colony Room Club where painters, poets and actors gathered: Francis Bacon, Lucien Freud, John Osborne, George Barker, Elizabeth Smart, Beryl Bainbridge, Tom Baker and John Hurt among them. Bernard’s columns are littered with memories and anecdotes of many of them. He writes of a Soho that was, even in his day, slowly dying and that has by now faded into history as corporate interests and rising rents have pushed the old Soho aside and replaced it with the homogenised, sanitised streets that can be found almost anywhere. Soho’s face has been wiped clean of its louche individuality.

Bernard’s own drinking was prodigious, and it did occasionally undermine his career as a journalist. He was famously sacked by Sporting Life as a result of his drunken behaviour the precise details of which are never fully revealed. On the occasions when he was unable to deliver his weekly column to The Spectator on time, they would simply note in the magazine that “Jeffrey Bernard is unwell”. Despite his lifelong dedication to the consumption of alcohol and his sometimes outlandish behaviour his editors appear to have been a rather tolerant bunch and he was able to maintain a reasonably successful career as a journalist. This can only have been because of the quality of his writing and the sharpness of his wit.

Bernard’s health, though, was certainly affected by his heavy consumption of alcohol which at one point is said to have been as much as a bottle and a half to two bottles of vodka a day. The cartoonist Michael Heath is credited with noting that Bernard’s hobby in life was the observation of his own physical dissolution and towards the end of his life there is certainly an increased preoccupation with his declining health in his columns. He suffered from pancreatitis and diabetes which led to his having a leg amputated below the knee. On that occasion The Spectator noted “Jeffrey Bernard has had his leg off”.

He treats his own ill health, and it’s causes, with the same wit and clear-eyed honesty as he does everything he writes about in his columns and while there is some self-criticism and even some sadness, there is little bitterness. He is appreciative of the care he receives from the NHS and writes amusingly, but mostly compassionately, about his fellow hospital patients. He is equally appreciative of the help he receives from the friends that rally round when he needs them.

Re-reading his columns all these years later I have been surprised at how much I enjoyed them. I think the reason for that is that while he can be acerbic, grumpy and irritable he directs his grumpiness at himself as much, if not more so, as he does towards others, and he always seems to be honest and fair in his criticisms. I enjoyed this book a lot although I have to say that it is a book to be dipped into rather than one to be read from cover to cover.

I would like to express my thanks to NetGalley and Duckworth for making a free download of this book available to me.

Readers who liked this book also liked:

Ling Ling Huang

General Fiction (Adult), Humor & Satire, Multicultural Interest