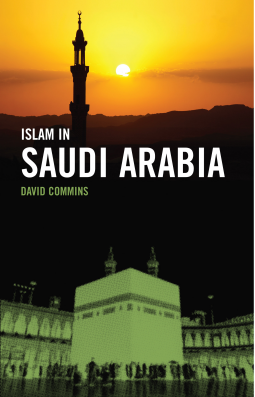

Islam in Saudi Arabia

by David Commins

This title was previously available on NetGalley and is now archived.

Send NetGalley books directly to your Kindle or Kindle app

1

To read on a Kindle or Kindle app, please add kindle@netgalley.com as an approved email address to receive files in your Amazon account. Click here for step-by-step instructions.

2

Also find your Kindle email address within your Amazon account, and enter it here.

Pub Date May 01 2015 | Archive Date May 18 2015

Description

"Royal power, oil, and puritanical Islam are primary elements in Saudi Arabia's rise to global influence. Oil is the reason for Western interest in the kingdom and the foundation for commercial, diplomatic, and strategic relations. Were it not for oil, the government of Saudi Arabia would lack the resources to construct a modern economy and infrastructure, and to thrust the kingdom into regional prominence. Were it not for oil, Saudi Arabia would not be able to fund institutions that spread its religious doctrine to Muslim and non-Muslim countries. That doctrine, commonly known as Wahhabism, is a puritanical form of Islam that is distinctive in a number of ways, most visibly for how it makes public observance of religious norms a matter of government enforcement rather than individual disposition and social conformity, as it is in other Muslim countries."—from the IntroductionSaudi Arabia is often portrayed as a country where religious rules dictate every detail of daily life: where women may not drive; where unrelated men and women may not interact; where women veil their faces; and where banks, restaurants, and cafés have dual facilities: one for families, another for men. Yet everyday life in the kingdom does not entirely conform to dogma. David Commins challenges the stereotype of Saudi Arabia as a country immune to change by highlighting the ways that urbanization, education, consumerism, global communications, and technological innovation have exerted pressure against rules issued by the religious establishment.Commins places the Wahhabi movement in the wider context of Islamic history, showing how state-appointed clerics built on dynastic backing to fashion a model society of Sharia observance and moral virtue. Beneath a surface appearance of obedience to Islamic authority, however, he detects reflections of Arabia's heritage of diversity (where Shi’ite and Sufi tendencies predating the Saudi era survive in the face of discrimination) and the effects of its exposure to Western mores.

Advance Praise

"An eye-opening account, clearly written, subtly argued."—James L. Gelvin, UCLA, author of The Arab Uprisings: What Everyone Needs to Know and The Modern Middle East: A History

Available Editions

| EDITION | Other Format |

| ISBN | 9780801456916 |

| PRICE | $19.95 (USD) |

Links

Featured Reviews

Joseph S, Reviewer

Joseph S, Reviewer

Islam in Saudi Arabia by David Commins is clearly written history of Saudi Arabia and the role religion plays in society and national and international politics. Commins is Professor of History. He earned his B.A. at the University of California, Berkeley, and his Ph.D. from the University of Michigan. He has received Fulbright grants to fund Arabic study at Damascus University (1981-82), to research Islamic modernism in Ottoman Syria (1982-1983), and to study Wahhabism in Saudi Arabia (2001-2002).

I lived in Saudi Arabia for about eighteen months in 1984-1986 and served as a Marine Guard at the American Embassy. I remember the experience well and even then the conflicts between the proper religious behavior and reality. For example, there was a music store that sold bootleg cassette tapes of questionable quality for under a dollar. The store was allowed to function and most music was available. However, the religious pressures had the store remove Michael Jackson's Thriller after the younger generation took to wearing a single glove and moonwalking in their thobes.

One thing that is very noticeable in Saudi Arabia and discussed by Commins are the high walls surrounding houses. People have a public and a private life. Inside the walls, many Saudis live Western lives -- jeans, television, music. The religious authorities are not allowed to climb the walls and peer over them as that is a violation of the well-established Islamic law. Many use this same method to keep satellite dishes out of view.

Commins examines the many dichotomies of Saudi Arabia. It goes deeper than the public and life of the population. There is a very different interpretation of church and state in the country too. Both the religious (clerics) and the government (Saud family) struggle for power. Many times the confrontations are handled with dialog other times violence. Television for example (and later the internet) were brought into question. Islam prohibits any representation of living beings Television both use images of people which would generally be called idolatry under the Wahhabi Sunnism practiced in Saudi Arabia. Television was introduced in 1965 and ended with protests including a death of a nephew of King Faisal. The government bowed to religious pressure to allow the clerical class to determine all programming. The debate ended with a fatwa allowing television because the good of religious programming outweighed the possible bad. Now, with the addition of satellite TV and the internet, the religious authorities can no longer keep up with censorship.

The royal family divided government with the clerics to keep the most radical ideas out of foreign affairs and economics. The government gave control of religion and education to the clerics and remained in control of outward policies. This gives the US a friendly ally in Saudi Arabia officially while the population may contribute money and people to causes against the United States: Bin Laden came from a wealthy Saudi family. Fifteen of the 9/11 hijackers came from Saudi Arabia.

Saudi Wahhabism is a very strict form of Islam and if the country was controlled by the clerical class it would be a far different place. It is the moderation of the ruling family that allowed Saudi Arabia to enter the modern world and advance into the modern world of states. Much of this has been because the ruling family has stood up to the clerics by allowing infidels on the Islam's soil first as oil workers and most recently in military bases against the Iraqi threat. Even in high-walled compounds to hide the visible presence of outsiders, it has not always gone smoothly -- the Khobar Tower bombings, for example.

Islam in Saudi Arabia gives a detailed, but a very readable history of Saudi Arabia and the role of Islam throughout that history. I have only touched on a few points brought up in the book, most that related to either my time there or studies in foreign policy. Books like this that will go a long way in improving America’s understanding of Islam and Saudi Arabia. The battle inside Saudi Arabia is just as important to understanding its actions on the world stage and its relations with its allies. Saudi Arabia is in a struggle with itself. The struggle is growing more visible as modern technology is opening the outside world to the younger generation, but the clerics controlling the education. The struggle is also with its neighbors. Saudi has a Sunni majority while Iran is Shiite; an Iran hegemon would not be beneficial to Saudi Arabia. Islam provides the unity of the Saudi people, but it also creates divisions when defining issues of human rights, national interest, and even evolving culture. Islam in Saudi Arabia is well worth the read and is very helpful understanding the complexity of a pivotal nation in one of the world’s politically and economically strategic areas.