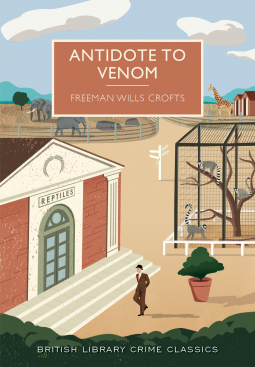

Antidote to Venom

A British Library Crime Classic

by Freeman Wills Crofts

This title was previously available on NetGalley and is now archived.

Send NetGalley books directly to your Kindle or Kindle app

1

To read on a Kindle or Kindle app, please add kindle@netgalley.com as an approved email address to receive files in your Amazon account. Click here for step-by-step instructions.

2

Also find your Kindle email address within your Amazon account, and enter it here.

Pub Date Jul 07 2015 | Archive Date Jul 13 2015

Description

George Surridge, director of the Birmington Zoo, is a man with many worries: his marriage is collapsing; his finances are insecure; and an outbreak of disease threatens the animals in his care.

As Surridge's debts mount and the pressure on him increases, he begins to dream of miracle solutions. But is he cunning enough to turn his dreams into reality - and could he commit the most devious murder in pursuit of his goals?

This ingenious crime novel, with its unusual 'inverted' structure and sympathetic portrait of a man on the edge, is one of the greatest works by this highly respected author. The elaborate means of murder devised by Crofts's characters is perhaps unsurpassed in English crime fiction for its ostentatious intricacy.

This new edition is the first in several decades and includes an introduction by the award-winning novelist and crime fiction expert Martin Edwards.

Available Editions

| EDITION | Other Format |

| ISBN | 9781464203794 |

| PRICE | $12.95 (USD) |

Average rating from 18 members

Featured Reviews

Janet P, Reviewer

Janet P, Reviewer

Freeman Crofts is an often-overlooked author of the "Golden Age" of British dective stories. This new series from Poison Pen Press is bringing many of these classics back into print.

This volume is a great addition to the series for many reasons.

First it is a double mystery. The first part of the book is told from the point of view of the criminal, azoo director who is having money troubles. After the crime and inquest, the second part of the book focuses on the re-opened investigation and Crofts' main dectective Chief Inspector French of Scotland Yard.

Second, it's a great crime, almost perfect. It's complex, but not unbelievably so. The criminals are smart and cover their tracks well. The result of the inquest is satisfactory. But French has a very innocent question that leads him to investigation and, finally, to the correct solution.

Third, the concluding chapter looks at what happens to the criminal after conviction. Few novels go to this point. Although the writer of the introduction finds this a fault, I liked it. We find mysteries satisfying because the balance of the world is upset by the crime. The job of the dectective is to rebalance by discovering the solution to the crime. But almost always it leaves out the criminal and the lack of balance in his soul that led to the crime.

Crofts' concern both for the more psychological aspects of his characters as well as his concern for their souls looks at this aspect and creates a satisfying conclusion.

Readers who liked this book also liked:

We Are Bookish

General Fiction (Adult), New Adult, Romance

We Are Bookish

LGBTQIAP+, Romance, Sci Fi & Fantasy

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Comics, Graphic Novels, Manga, Mystery & Thrillers, Teens & YA

Elle Cosimano

General Fiction (Adult), Mystery & Thrillers