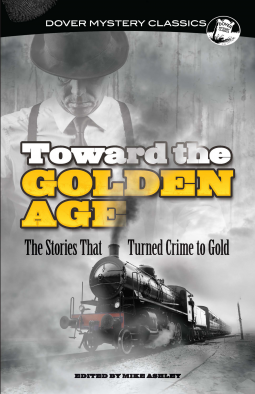

Toward the Golden Age

The Stories That Turned Crime to Gold

by Mike Ashley

This title was previously available on NetGalley and is now archived.

Send NetGalley books directly to your Kindle or Kindle app

1

To read on a Kindle or Kindle app, please add kindle@netgalley.com as an approved email address to receive files in your Amazon account. Click here for step-by-step instructions.

2

Also find your Kindle email address within your Amazon account, and enter it here.

Pub Date Aug 17 2016 | Archive Date Nov 16 2016

Description

Unconventional characters add to the appeal of these tales: Father Brown, G. K. Chesterton's priest and amateur sleuth, makes his first-ever appearance in "The Blue Cross"; Lady Molly of Scotland Yard, one of fiction's first women detectives, solves "The Ninescore Mystery" by Baroness Orczy; November Joe, Hesketh Prichard's backwoods shamus, investigates "The Crime at Big Tree Portage"; and blind detective Max Carrados exhibits his mastery of "The Game Played in the Dark" by Ernest Bramah. Editor Mike Ashley provides individual introductions to these and other stories, offering intriguing insights into the emergence of the Golden Age of the detective story.

Available Editions

| EDITION | Paperback |

| ISBN | 9780486806099 |

| PRICE | $9.95 (USD) |

Average rating from 2 members

Featured Reviews

Leyla J, Reviewer

Leyla J, Reviewer

I really enjoy these anthologies, there are a lot available out there, but this ones presented by Michael Ashley add another dimension with little biographies prior to each story. Yes this is a set of short stories from the writers of crime, there are fifteen writers with wonderful, varied stories in the mix, including works by Wells, Baroness Orczy, Rinehart, Reeves and others. They are not full of sex or violence, but tell a story and puzzles that make you think. I really enjoyed it.

The fifteen mystery short stories here range from terrible to pretty good, and from rare (likely not to have been read even by mystery enthusiasts) to uncommon (have appeared in a few anthologies over the years, but are not standards). The main reason for four stars is the collection along with the editor's comments shed interesting light on the transition from 19th century magazine story crime fiction to the detective novels of the 1920s and 30s. Thus I recommend this book primarily for readers interested in the history of the mystery. Other readers will find uneven quality.

Looking at a list of the 100 greatest mystery novels of all time, only seven were written before 1900. All were by famous writers who happened to choose crime as a subject for one or two books: Edgar Allan Poe, Wilkie Collins, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Charles Dickens, Bram Stoker and Arthur Conan Doyle (in the 20th century Doyle would write more Sherlock Holmes novels and today is remembered primarily for Holmes, but he was a prolific writer in other genres). Two of the books were collections of magazine short stories, the others were serialized in magazines. The books are wildly different, none followed the conventions of Golden Age fiction.

In contrast, 29 of the 100 books were published at the height of the Golden Age, in the decade from 1929 to 1939. The authors are all known as mystery specialists: Agatha Christie, Anthony Berkeley, Daphne du Maurier, Dashiell Hammett, Dorothy Sayers, Eric Ambler, James M. Cain, John Dickson Carr, Michael Innes, Nicholas Blake and Raymond Chandler. All the books were original published in novel form. While there are differences in tone and style, the books fall pretty neatly into the conventions of classic English mysteries, hard-boiled American novels or spy fiction.

This collection covers the period from 1905 to 1921 when short stories were giving way to novels and magazine publication to book. The popularity of the genre was exploding, and the field became increasingly dominated by specialist writers. Melodrama, philosophy and horror were declining in favor of character and science. Stories got lighter and concentrated more on comfortable educated middle-class officials, rather than the poor and desperate or aristocratic protagonists of earlier stories. Conventions were forged that are still relevant today, although modern books are as likely to defy the conventions than uphold them.

Five of the stories (The Case of Oscar Brodski by R. Austin Freeman, The Blue Cross by G. K. Chesterton, The Man Who Lived at Clapham by Edgar Wallace, The Ninescore Mystery by Baroness Orczy and The Papered Door by Mary Roberts Rinehart) are early works by writers who would thrive in the Golden Age, although not all as mystery specialists. These are the best written ones in the book. Each one includes an element that would become a staple of Golden Age fiction, but in other respects is more similar to 19th century stories. Their main defect as stories is their over-reliance on the single element, but from a historical perspective this is interesting as we see the element in the process of invention.

Four mysteries (The Crime at Big Tree Portage by Hesketh Prichard, The Tragedy on the London and Mid-Northern by Victor Whitechurch, Spontaneous Combustion by Arthur Reeve, The Case of the Scientific Murderer by Jacques Futrelle) are by lesser writers who happened to be fanatics about one thing or another. Only Prichard knew much about his obsession, and while his story lacks either plot or character interest, it's worth reading for the account of backwoods survival. The other stories are even worse in overall literary terms and even more objectionable for their absurdities. Jacques Futrelle is the worst as his detective insists obnoxiously about his deep knowledge of science while peddling arrant nonsense. For one example (this is a semi-spoiler, but the point is revealed fairly early in the story and is so stupid it cannot be spoiled), he has characters murdered by having a bottle with a vacuum inside pressed to their lips. He gives the diameter of the bottle mouth as 1.25 inches, which means a perfect vacuum inside the bottle takes as much effort to pull off as lifting 18 pounds, and you only have to move the bottle a fraction of an inch to break the seal. Even if the victim is too weak for that, all she has to do is expel some of the six liters of air in her lungs. The size of the bottle is not given in the story, but it appears to be something like one liter. If that doesn't work, all she has to do is breathe through her nose, breathe through the side of her mouth or block the bottle opening with her lips or tongue.

While these stories are little pleasure to read, they do demonstrate how factual material was introduced into mysteries, chasing out the supernatural and the conventional. This set the stage for Golden Age authors who either were experts or consulted experts, and wove the material tightly into their stories.

Other lesser efforts are more entertaining. Christabel's Crystal by Carolyn Wells got slightly mangled, but nevertheless is a lightly amusing parody that anticipated the classic manor house mystery. Naboth's Vineyard by Melville Davisson Post is a poor mystery, but a fascinating glimpse of Southern antebellum popular democracy. It realized the dramatic potential of a courtroom thriller, although without the tight plotting necessary for that genre. The Game Played in the Dark by Ernest Bramah is an early example of the handicapped detective. Although a ridiculous story on all levels, it has the shining virtue that the author credibly manages to turn the handicap to an advantage, something that is usually managed incredibly, or else forgotten. Whither Thou Goest by Edward Hurlbut got seriously mangled, and is nearly unintelligible. The individual elements are very strong, however, and it is as hard-boiled as anything from the Golden Age. I wish someone would either locate the original manuscript (assuming the mangling was done in magazine publication) or rewrite this story. The Second Bullet is another terrible mystery, partly redeemed by some strong characterization.

What this last group illustrates is how hard it was to combine the elements that went into Golden Age mysteries. Each author grasped the importance of one element or another, but failed to integrate it into a good mystery. It's easy to overlook the craftsmanship necessary for classic mysteries because after it was finally done properly, it became conventional (in fact, is was that conventionality that doomed the genre after WWII, although it remains influential).

Overall, this is a collection of one-star to four-star stories, with historical interest above its literary quality.

AliceMaud M, Reviewer

AliceMaud M, Reviewer

I have enjoyed reading this collection of short stories not least because of the informative introduction provided for each one by the compiler, Mike Ashley. The introductions tell the reader something about the authors, many of whom I had never heard of previously and some of whom I associated with genres other than detective fiction, and also put the stories themselves in perspective, for example, comparing and contrasting plots with those of earlier authors such as Conan Doyle, or citing relevant scientific advances.

I thought that the short stories themselves varied in quality and interest, which, to be honest, is most often my reaction to an anthology and probably means that there is something for everyone in this collection, The book would be a useful textbook for someone interested in the development of detective fiction, and also a good candidate for a reading group or club.