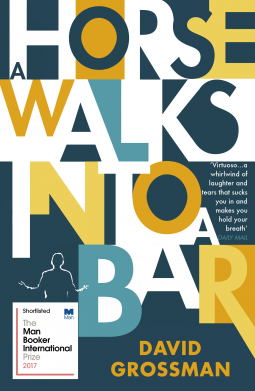

A Horse Walks into a Bar

by David Grossman

This title was previously available on NetGalley and is now archived.

Send NetGalley books directly to your Kindle or Kindle app

1

To read on a Kindle or Kindle app, please add kindle@netgalley.com as an approved email address to receive files in your Amazon account. Click here for step-by-step instructions.

2

Also find your Kindle email address within your Amazon account, and enter it here.

Pub Date Jun 16 2017 | Archive Date Sep 18 2017

Description

WINNER OF THE INTERNATIONAL MAN BOOKER PRIZE 2017

The setting is a comedy club in a small Israeli town. An audience that has come expecting an evening of amusement instead sees a comedian falling apart on stage; an act of disintegration, a man crumbling, as a matter of choice, before their eyes. They could get up and leave, or boo and whistle and drive him from the stage, if they were not so drawn to glimpse his personal hell. Dovaleh G, a veteran stand-up comic – charming, erratic, repellent – exposes a wound he has been living with for years: a fateful and gruesome choice he had to make between the two people who were dearest to him.

A Horse Walks into a Bar is a shocking and breathtaking read. Betrayals between lovers, the treachery of friends, guilt demanding redress. Flaying alive both himself and the people watching him, Dovaleh G provokes both revulsion and empathy from an audience that doesn’t know whether to laugh or cry – and all this in the presence of a former childhood friend who is trying to understand why he’s been summoned to this performance.

Available Editions

| EDITION | Other Format |

| ISBN | 9781784704223 |

| PRICE | £8.99 (GBP) |

| PAGES | 208 |

Featured Reviews

Greg Y, Reviewer

Greg Y, Reviewer

A Horse Walks Into a Bar is undeniably dark. It focuses on a stand-up comedian telling the tale of his miserable life in the face of an increasingly hostile crowd that just wants light entertainment. It is claustrophobic; the action hardly departs from the small-town nightclub Dovaleh is performing in, other than through his reminiscences. It is uncomfortable, as Grossman places us firmly in the audience watching this man fall apart, through the eyes of an old acquaintance that Dovaleh has asked to attend. The reader squirms right along with the audience and the performer as his attempts to get through his tale fall flat, or even provoke outrage. It is compelling, as the novel forces you to choose between walking out on Dovaleh's act. like some of the characters, or staying the course to hear the final punchline. It is also funny; some of the jokes that Dovaleh delivers in the course of his monologue cracked me up.

Coming from a city and country where stand-up comedians are an integral part of our popular culture, I was attracted to this book's premise, and I wasn't disappointed. I have seen shows like Dovaleh's, where the comedian departed from jokes and ventured into the deeply personal, and I've seen the audience response. I've seen guys walk out of a comedian's account of his experience with multiple sclerosis because it wasn't funny enough for them. Grossman captured this awkward "should we really be laughing?" dynamic perfectly, and gives us a perfect rendition of a quintessential sad clown.

Flavia B, Reviewer

Flavia B, Reviewer

This was not an easy book to read; which sounds contradictory and ironic since it is book structured around a stand up comedy sketch. The novel tentatively feels its way along the boundaries between what is funny and what isn’t, slipping and sliding in and over each other; eventually collapsing the one into the other in a grotesque heap. The pull and loosening of tension provides an incredible rollercoaster read.

The novel deals with our boundaries with others; people who we loved that we carry within, our need for people/affection but also our need to be separate. It is also a story about our expectations and the chaos and unpredictability of life and the horror of tragedy in a child’s past (which seeps in from the horror of his parent’s life). I really laboured to read this initially; my reflections mirrored in the narrator’s (the judge’s) own struggle throughout (bringing his own tragedy and pain to the show/novel with him). This is what we do as readers/audience/spectators’ – we let performances/books wash over us but they are unable to wash away our own internal pain completely.

There was a dichotomy between audience and myself, as reader, in this novel; while the audience wanted jokes, I, as reader, was drawn towards the unravelling of the story of Doveloh’s first funeral (in spite of the pain and rawness of it all).

Dovaleh’s comedy is vulgar, abusive at times and we are repelled by the comedian, he has been seriously unwell (physically and mentally), which explains why he comes undone, why he chooses to come undone under the eyes of the judge, his childhood friend. He becomes the ugly face of truth when comedy and tragedy are stripped away.

Dovaleh falls apart through a story which actually pieces together who he is/has become/has lived. He explains why he has turned to comedy; he remembers how he liked to make his suffering mother laugh; only he could make her smile that particular way when as a child he did private shows for her. He goes into great detail about the driver who during the defining moments of Dovaleh’s abject misery (as he hurtles towards certain grief) unthinkingly turned to comedy as distraction.

The audience in the novel often acts as a whole but also splinters off into the diverse people, and their own set of demands and needs from the evening. The audience take turns in sustaining or turning against him. Grossman displays the power of a comedian in providing a choreography; pumping up his audience, reeling them in, letting them go and the audience’s own need to forget themselves and be one of a crowd.

Only the judge himself has been personally invited by Dovaleh. To observe, as we do. He sees Dovaleh through his own memories, as he is now and through his own grief, even filters his judgement through his wife’s criticism, he feels her within him. His grief is a very live thing and this binds him to Dovaleh.

Apart from the judge, the other important audience member is a woman who also knew Dovaleh as a child. A misfit herself (she is small, she has a speech impediment, ironically her feet don’t touch the ground), she is manicurist and medium and yet provides the grounding/realist/grim view to Dovaleh’s comedy. She has no sense of humour and battles for literal truth; she is rooted in the reality of Dovaleh’s childhood self before he had to mask himself/his pain or build up the barrier of comedy. She sees him for what he is and denies his comedy and his meanness thereby causing a catalyst to his coming undone (indeed her initial conversation with Dovaleh is a pivotal point to his stand up comedy sketch), or to the only story he needed to tell. She, like the judge, is taking notes. She battles for literal truth and in this way Dovaleh is completely exposed and debilitated in front of her. The judge sees her as Eurycleia (Odysseus’ elderly nanny) because she was able to recognise Dovaleh’s true self via his scar/the wound that was his childhood.

Grossman is brilliant in displaying Dovaleh’s own internal and external battle – often through physical violence (self inflicted, the punchline itself!) and through his words. He has a childish impulse to tally up, like he had done so in his drive to the funeral. Tallying up has caused the biggest scar in Dovaleh’s life and is also represented by the blackboard (which indicates some sort of premeditation, along with his request that the judge be present and the fact that this is his birthday and consequently somehow a symbolic day for Dovaleh). This need for control over what he can’t control reflects the first tally he made that has infected and poisoned his whole life.

The title ‘A Horse Walks into a Bar’ refers to a joke the driver begins to tell Dovaleh as he travels towards the truth and the horrible internal battle rages inside him. He doesn’t tell us the punch line, instead the narration swerves into Dovaleh’s internal hell and the narrator’s own self questioning.

This is a novel of desperation, grief and loss but ultimately it is also a story about the redeeming nature of friendship.

Moray L, Librarian

Moray L, Librarian

Once again David Grossman reveals his genius for creating hugely affecting and yet appalling characters. The premise is quite simple. The narrator (court judge Avishai Lazar) has been invited to watch a stand-up performance by a man he briefly knew as a boy. This performance, recorded “verbatim” along with reactions from the audience and reminiscences by the narrator. As the show develops it becomes increasingly and intensely personal as the comic relates a painful event from his childhood. Sometimes he plays this for laughs with the blackest of humour but increasingly loses his hold on his comedy and his audience. It is a slow but inevitable collapse of a routine and a man. Simple, yes, but easy? No. There are very few writers with the vision and the control necessary to make such a narrative a success but Grossman is one of them.

There were times when I hated this book. I hated the crassness of many of the jokes, the casual prejudice, a deep unpleasantness in the way Dovaleh Greenstein plays the tragedy and cruelty of the Arab-Israeli conflict for cheap laughs and thinks nothing of stooping to the lowest common denominator. But this is precisely where Grossman’s talent shines because it is a pitch-perfect rendering of the best and worst of stand-up comedy with all the pitfalls and pratfalls laid bare. After all there is something deeply (if not always commendably) human in our capacity to make a (bad) joke out of anything. Anything for a laugh.

One Grossman’s great talents is his facility for placing the ridiculous and the painful side by side so that both are heart-breaking. By interspersing the sometimes humorous often uncomfortable ranting of Davoleh and his sudden bursts of self-contempt and violence, with the memories of his former friend and current audience-member we form a complex picture of a deeply flawed man. It is natural to despise him but Grossman won’t let you rest on that, he will not let you take the easy way out. As he spins out the story of his life the unpleasantness of his character and manner become less about a person and more about the tragedy of lives spoilt by conflict and propaganda and a context which seeks to destroy the ability to feel compassion and empathy. Davoleh is a product of his surroundings and his experience and that is the really tragic joke.

“How did [Davoleh] do that?” Lazar wonders at one point “How, in such a short time, did he manage to turn the audience, even me to some extent, into household members of his soul? And into his hostages?”. One might wonder the same about Grossman who can push and prod you to the very edge of giving up in disgust and always reel you back in

Well, I rattled through this one. A Horse Walks into a Bar is a book that grabs you and takes you with it whether you want to go or not. And some of the time I wasn’t sure if I did want to go. Dov G is an Israeli comedian of the type that insults his audience – think Lennie Bruce but not so blue, or Frankie Boyle but not so political. He homes in on his audience’s frailties and picks at scabs – both theirs and his own.

His old friend from schooldays, now a reired Judge, has come to Netanya to see Dov’s performance. The pair haven’t seen each other for 40 years but Dov has begged the Judge to come and tell him what he sees. Is there something in everyone that cannot be hidden? If so, the Judge with his experience of studying defendants will be able to see it. In the crowd is a tiny woman who also knew Dov as a child. He was nice to her then but isn’t now. She cries at his barbed comments but refuses to leave.

When the jokes come they are not always funny and even when they are there is an unpleasant background taste. Along with his stand-up Dov tells the tale of how he went to his first funeral, even though he didn’t know who had died. The audience get restless; some leave. Those remaining call for more laughs. This is not what they paid to see.

While Dov strips himself and the crowd bare, the Judge recalls his own shameful part in an incident for which he is sure Dov will excoriate him before long. He also reminisces about his dead wife. He eats and drinks but cannot seem to fill himself up.

Dov’s jokes get fewer and less funny and more people leave. The tables in the supper club are emptying. The tiny woman, Pitz, is still there and a few other stalwarts. Dov punches himself, punishes himself, makes himself bleed. The revelation of the cause of his self-hatred is not totally unexpected but still, it could have been otherwise. He wipes the sweat from his brow, says ‘Goodnight Netanya’ to the almost empty club, and finishes what is probably his last ever performance.

This is an unusual and brilliant book. The stage show is presented visually so that we see Dov’s very physical performance. We feel his sweat and his pain. We dislike him but cannot stop watching him. Ultimately, there may be some kind of redemption – for him and the Judge.

Readers who liked this book also liked:

Nigel Henbest; Simon Brew; Sarah Tomley; Ken Okona-Mensah; Tom Parfitt; Trevor Davies; Chas Newkey-Burden

Entertainment & Pop Culture, Humor & Satire, Nonfiction (Adult)