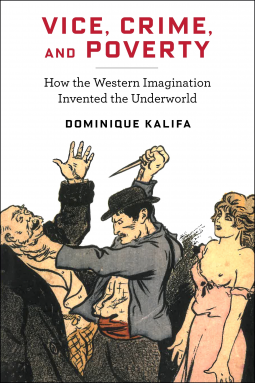

Vice, Crime, and Poverty

How the Western Imagination Invented the Underworld

by Dominique Kalifa

This title was previously available on NetGalley and is now archived.

Send NetGalley books directly to your Kindle or Kindle app

1

To read on a Kindle or Kindle app, please add kindle@netgalley.com as an approved email address to receive files in your Amazon account. Click here for step-by-step instructions.

2

Also find your Kindle email address within your Amazon account, and enter it here.

Pub Date Apr 16 2019 | Archive Date Jul 31 2019

Talking about this book? Use #ViceCrimeAndPoverty #NetGalley. More hashtag tips!

Description

In Vice, Crime, and Poverty, Dominique Kalifa traces the untold history of the concept of the underworld and its representations in popular culture. He examines how the myth of the lower depths came into being in nineteenth-century Europe, as biblical figures and Christian traditions were adapted for a world turned upside-down by the era of industrialization, democratization, and mass culture. From the Parisian demimonde to Victorian squalor, from the slums of New York to the sewers of Buenos Aires, Kalifa deciphers the making of an image that has cast an enduring spell on its audience. While the social conditions that created that underworld have changed, Vice, Crime, and Poverty shows that, from social-scientific ideas of the underclass to contemporary cinema and steampunk culture, its shadows continue to haunt us.

Advance Praise

"Dominique Kalifa is one of the best French cultural historians of his generation and a worthy successor to Alain Corbin at the Sorbonne. Vice, Crime, and Poverty examines the urban ‘underworld,’ not in the twentieth-century sense of organized crime but as an imaginary shaped discursively in the nineteenth century by a widespread if morbid fascination with the apparent dangers of urban life."

-Edward Berenson, author of Europe in the Modern World

Available Editions

| EDITION | Other Format |

| ISBN | 9780231187428 |

| PRICE | $130.00 (USD) |

Average rating from 6 members

Featured Reviews

nathan h, Reviewer

nathan h, Reviewer

Just think for a minute about what comes to mind when you think of the term "underworld": You'd get a wide swath of images, ranging from dark alleys were some indulge in desires and/or waste away, or to movies about vampires fighting werewolves, right? Probably some manner of Dickensian setting appears? Kalifa's work (fantastically translated by Susan Emanuel) means to educate on how this "state" of the underworld came to be in our collective imagination. How much of it was romanticized? What's changed over the years, and what have these underserved parts of cities come to inspire and inform?

Aside from adequately acquainting you with the terms "bas-fonds" and "milieu" (apparently it's no use to try to obtain a stout definition of the latter), we're given a selective tour of history throughout major cities (usually Paris, London, and New York) as they all slowly develop underbellies; some due to the oppressed proletariat, citizens in poverty having to resort to whatever means necessary to live, others being held all but against their will in zones while government programs sort them out---any/all of the previously mentioned, and so much more. I say "so much more" because Kalifa has put together what has to be one of the most thoroughly researched books I've ever read (maybe that's an indictment on me, but if he's impressed anyone, he can count me among them). Populated with example upon example upon example, the layers begin to thread through each other and form a tapestry of a recognizable environment instantly bringing to mind works popular to this day (Les Miserables, for instance).

I grew up hearing the phrase "slumming it up", probably like most everyone else---hell, I use it to this very day, but I couldn't have told you what it meant until I read this.

As with any book that's heavy on the examples and clipping itself to so much evidence, you're in for the experience of a dense read. Keep at it, though, and you'll be rewarded. Think about it: Kalifa has produced a great resource to discover the background for the real-life places that have inspired countless forms of good despite their reputations, going from the FDA to even Batman (by way of Detective Comics)! Can't find something to link those two anywhere else.

Many thanks to NetGalley and Columbia University Press for the advance read.

Reviewer 542906

Reviewer 542906

In Vice, Crime, and Poverty, Dominique Khalifa explores whether representations of the “lower depths”, or “underworld”, in personal accounts reflected historic reality.

The expression “lower depths” comes from French and, unlike the opening sentences of the book suggest, it is not easily associated with the underworld for most native English speakers. I understand that this book was translated, but I do feel like this could have been changed from the original, simply because it instantly put me off, making me think I could not relate at all.

As someone tangentially familiar with the topic - I’ve previously studied the perceived degeneracy of the masses during British industrialisation - this was a pretty interesting and engaging book. It was well-written and showed strong academic structure, however it was a bit too emotive (“frightful world”, “without shuddering or flinching”) for what appeared to be an academic text. It is is definitely more oriented towards academic readers than casual readers. While it is well-written and explains most unfamiliar terms, it’s dense and isn’t easily accessible for anyone outside of the field of history or social studies.

That said, I did engage well with the content, it had a good natural progression and quotes from personal accounts were included seamlessly. I enjoyed it and I’d be interested to see if there is anything else by the author that matches my subject interests as well.

An exploration into the historical imaginary of the "underworld" of the poor neighborhoods of major cities of the Western world.

The author does not focus as much on the actual lived experience of life in poor neighborhoods in major urban areas in Western Europe and the United States as the stories which were written about such areas. The author begins with a history of the conception of people in poor areas of towns, from medieval concerns about vagabonds to the development of the view of a seedy "underworld" orchestrated into its own sub-cultural state as promulgated in books and papers in the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries. The author explores the morbid fascination of the upper middle class and the elites in society regarding how the "underworld" lived: how they consumed books and articles on the subjects of life and crime in poor areas, would participate in guided tours of such neighborhoods, yet all the while maintaining their distance and finding sufficient reasons for moral approbation. The author chronicled the societal changes in attitudes about the poor and how the whole "underworld" concept would eventually shift considerably in the 20th century away from being a neighborhood dependent thing into associations which were centered in far "nicer" areas.

Much more is made of Paris than London or New York, as befits the author's primary focus. Yet the author does well to demonstrate the validity of his thesis that the "underworld" of poor people reveling in and saturated with vice and crime was mostly an imagined construct. Yes, there was vice and crime in poor areas, and it perhaps was more pervasive than in other realms; nevertheless, the wealthier were generally more interested in profiting from it, exploiting it, and justifying themselves and their distance from it than being honest about it or doing much to help the situation. Creating the imaginary of the highly orchestrated underworld in seedy neighborhoods did its work to establish effective distance and justify moral approbation towards the poor and feelings of superiority among those who were not.

Thus, most of what we think about the experience of urban slums is not historically accurate. A sobering read indeed.