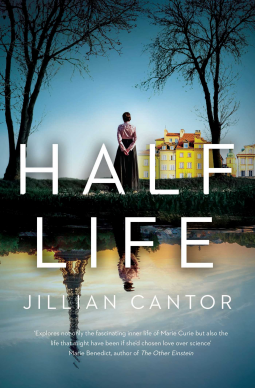

Half Life

by Jillian Cantor

This title was previously available on NetGalley and is now archived.

Send NetGalley books directly to your Kindle or Kindle app

1

To read on a Kindle or Kindle app, please add kindle@netgalley.com as an approved email address to receive files in your Amazon account. Click here for step-by-step instructions.

2

Also find your Kindle email address within your Amazon account, and enter it here.

Pub Date Apr 07 2021 | Archive Date Mar 31 2021

Talking about this book? Use #HalfLife #NetGalley. More hashtag tips!

Description

Poland, 1891. Marie Curie (then Marya Sklodowska) was engaged to a budding mathematician, Kazimierz Zorawski. But when his mother insisted Marya was not good enough, he broke off the engagement. A heartbroken Marya left Poland for Paris to study chemistry and physics at the Sorbonne. Marie would go on to change the course of science forever and become the first woman to win a Nobel Prize.

But what if Marie had made a different choice?

What if she had stayed in Poland, married Kazimierz, and never attended the Sorbonne or discovered radium? What if Marie had chosen her first love and a life of domesticity, still ravenous for knowledge in Russian Poland where education for women was restricted, instead of studying science in Paris and meeting Pierre Curie?

Seamlessly entwining the lives of Marya and Marie, Half Life is a powerful story of love and friendship, motherhood and sisterhood, fame and anonymity – and a woman destined to change the world.

Available Editions

| EDITION | Other Format |

| ISBN | 9781761100796 |

| PRICE | A$29.99 (AUD) |

| PAGES | 416 |

Featured Reviews

Cassie W, Reviewer

Cassie W, Reviewer

What a brilliant plot - to simultaneously explore the real life of Marie Curie and an imagined alternative life involving the same characters. It really did feel like I was reading about two different people at the beginning, but towards the end it became more difficult to separate which storyline I was reading. Perhaps that was intentional and speaks to the way we can grow into our identity as we experience life.

Themes of possibilities, decisions, consequences and regret are interwoven with questions of class, privilege, gender and identity. We always have choices but how do our circumstances limit the scope of those choices? How does our identity impact our choices and how do our choices affect the ongoing development of our identity? What is revealed about us by the sacrifices we are willing to make? Do we ever truly know what is happening in another person's life?

Underlying the complex plot and commentary on choices and consequences were recurring threads of loss and grief, not only for the death of loved ones, but for the life that could have been had different choices been made.

I was left reflecting on the choices that are available to me as a woman in 2021, compared to the more limited choices available to women in 1891. The story has much to say about how women were legally restricted in those times, but also points out the ways in which women can still find themselves being boxed into expected roles of motherhood and marital responsibilities, being asked to make choices that are rarely asked of men.

This was such a good read, extremely hard to put down and had me quite emotional a few times during the book.

It’s the story of Marie Curie’s life alongside the possible life she could’ve lived if Marya Sklodowska had never left Poland and married her first love, Kazimierz Zorawski. The couple were engaged but his mother didn’t approve of Marya and in real life a year or so later she leaves Poland to study in Paris.

The book is narrated in the first person, and the two streams (half lives?) alternate chapter by chapter. I thought the author did this skilfully and I was involved in the characters lives in both halves. It’s well researched and it must’ve been hard to keep the alternate life believable but it works.

The difficulties for women to study and work in these times is well explored, across time and countries. The difficulties of maintaining balance between family life and work especially for driven scientists like Curie; the sexism of the scientific community whether it be universities or even the Nobel prize (Pierre refused to accept unless Marie also got it) is astonishing but not surprising.

It is hard to read of all their experiments with radioactive materials completely unprotected without being horrified (Pierre gives Marie a radium nightlight!). It is unsurprising how much their health suffered.

An excellent, informative and emotional read.

Jillian Cantor Half Life Simon&Schuster 2021 (first published 2011)

Thank you NetGalley for this unproofed copy for review.

Jillian Cantor uses a familiar device – ‘sliding doors’, ‘what if?’ real and alternative lives – but that is as far as familiarity goes. What Cantor does with the device is truly captivating. The alternative stories of Marie Curie are full of characters that have an abundance of life, at the same time exploring what it means to be a woman dedicated to a range of attitudes, capacities and roles: wife, mother, career woman, widow and/or lover with experiences of loss, exhilaration, notoriety, fame and contentment.

The stories of Marya Sklodowska who takes the train to Paris to study at the Sorbonne and become Marie Curie, and the same Marya who instead marries Kazimierz Zorawski and remains in Russian Poland are developed in alternate chapters. Marya’s sisters, Bronia and Hela also have different lives as they also live their stories alongside Marie or Marya. Kazimierz becomes a major character with Marya, living frugally in Poland; in Marie’s story he marries well; Pierre Curie joins Marie in their laboratory and in winning the Nobel Prize. Minor characters are woven throughout the alternating stories, their life stories depending upon those of the main character, Marie/Marya.

Cantor explains her interest in the Marie Curie narrative as having a long history. Her interest in the character piqued long before she found the way in which she wanted to write the story. Her choice hinged on the scene that is so poignant in the fictional life – Marya does not climb aboard the train to Paris, she marries Kazimierz. However, it is the way in which the love affair between Marya and Kazimierz finishes that intrigued Cantor. His mother, for whom Marya worked as a governess to the younger children, did not think her good enough to become a family member. As Cantor says, ‘There was the fact that this amazing, brilliant woman, who would later go on to change the course of science and win two Nobel Prizes, was deemed not good enough as a young poor woman in Poland’.

Part of the charm and fascination in the novel is its settings. The status of women in Russian Poland provides the background to the ‘Flying University’ that Mayra creates. The university meets in its students’ homes with women teaching subjects with which they are familiar. Mayra, true to Marie, teaches science, she is poor at music, another class, and a profession that cleverly links with Marie’s story in Paris. The alternative story is that of an intelligent woman who must educate herself in a closed environment of Russian Poland where women are considered unworthy of education. Despite the restrictive atmosphere, the descriptions of Warsaw and Krakow are enticing.

Paris, Sweden and trips back to Poland feature in Marie’s story. But most important is the laboratory. And it is this that impacts on Marie’s relationship with her daughter – one that is at the same time understandable but also sad. In each of the stories, the attitudes towards family, children, partners, and the outside world are dealt with in detail. The women’s feelings of satisfaction and despair, Marie’s short-term desire to adopt a different approach to mothering, their relationships with others illuminate the way in which women’s choices are complex. The women are written in a way that creates empathy rather than judgment. Here, Cantor excels at using fiction to show the conflicts that feminist nonfiction works consider. There are no rules laid down, Marie Curie stands tall while Marya Zorawski, leading her different life, is also a character to be admired.

Half Life, although a scientific reference to the Curie’s Radium, seems to have more meanings within the novel. Marie’s impression of the light in her daughter’s eyes is a warmer, lighter side of the dedicated scientist. Light is a continuing theme in the Curie’s experimentation, illuminating the laboratory in the dark, and enlightening the world. At the same time, the ill health of both Curies and Marie’s death at sixty-six, with which the novel begins and ends, suggests that their work was responsible for the shortness of their lives. However, the dedication to their work, and each other, suggests that, although truncated, their lives were well lived. Cantor’s writing emphasises life, even when tragedies occur. The phrase could never be applied the lives led by Marie/Marya. Rather than half-lives, these women lived very full lives, the real one and the fictional version overlapping in some skillful writing and development of the fictional characters, in so many respects true to the real Marie Curie. The linkages between fact and fiction are deft and cleverly made. To return to my opening observation, Half Life is truly captivating.

‘What if…’

Maria Skłodowska had married Kazimierz Zorawski and never left Poland? As Marie Curie (7 November 1867 to 4 July 1934) she was a hero of mine: a scientist, the first woman to win a Nobel Prize and the only woman to win a Nobel Prize twice. I cannot imagine her life lived in any other way.

But Ms Cantor could. In this novel, Ms Cantor explores Marie Curie’s real life and imagines an alternative life which involves many of the same characters. The novel opens and closes with Marie on her deathbed, examining the choices she had made:

‘In the end, my world is dark. My bones are tired, my marrow failing. I have given my whole life to my work, but now, science brings me no comfort.’

This is ‘my’ Marie Curie: the scientist I admire. But there is always more to a life. I learned that in 1891 she had been engaged to Kazimierz Zorawski. Apparently, he broke off the engagement when his mother insisted that Maria Skłodowska was not good enough for him. Oh, the irony! What, I wonder, would Maria Zorawska have achieved?

The story shifts between the real Marie Curie and the fictional Marya Zorawska. I really enjoyed Marie Curie’s story but was less caught up in Marya Zorawska’s imagined life. I appreciated that Ms Cantor was showing some of the challenges posed within Poland (then under Russian control) for women. Educational opportunities for women were restricted, and Marya Zorawska was every bit as intelligent and driven as Marie Curie. I quite liked the alternate life imagined but I could not successfully envisage the same characters playing different roles in the different stories.

I would recommend this novel to anyone interested in Marie Curie as well as to anyone with an interest in the status of women in Europe in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

‘There was a choice. There was always a choice. Had I made the wrong one?’

Note: My thanks to NetGalley and Simon & Schuster Australia for providing me with a free electronic copy of this book for review purposes.

Jennifer Cameron-Smith