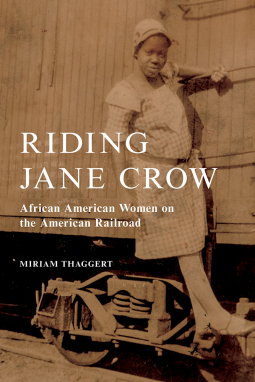

Riding Jane Crow

African American Women on the American Railroad

by Miriam Thaggert

This title was previously available on NetGalley and is now archived.

Send NetGalley books directly to your Kindle or Kindle app

1

To read on a Kindle or Kindle app, please add kindle@netgalley.com as an approved email address to receive files in your Amazon account. Click here for step-by-step instructions.

2

Also find your Kindle email address within your Amazon account, and enter it here.

Pub Date Jun 28 2022 | Archive Date Jul 01 2022

Talking about this book? Use #RidingJaneCrow #NetGalley. More hashtag tips!

Description

How Black women navigated train travel and Jane Crow from 1860 to 1925

Miriam Thaggert illuminates the stories of African American women as passengers and as workers on the nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century railroad. As Jim Crow laws became more prevalent and forced Black Americans to "ride Jim Crow" on the rails, the train compartment became a contested space of leisure and work. Riding Jane Crow examines four instances of Black female railroad travel: the travel narratives of Black female intellectuals such as Anna Julia Cooper and Mary Church Terrell; Black middle-class women who sued to ride in first class "ladies’ cars;" Black women railroad food vendors; and Black maids on Pullman trains. Thaggert argues that the railroad represented a technological advancement that was entwined with African American attempts to secure social progress. Black women's experiences on or near the railroad illustrate how American technological progress has often meant their ejection or displacement; and thus, it is the Black woman who most fully measures the success of American freedom and privilege, or "progress," through her travel experiences.

Miriam Thaggert is an associate professor of English at SUNY Buffalo and the author of Images of Black Modernism: Verbal and Visual Strategies of the Harlem Renaissance.

Advance Praise

"Riding Jane Crow brilliantly explores the experiences of Black women as passengers and workers on trains in post-Reconstruction America. This meticulously researched and well-written book takes the reader on a powerful journey that unveils the intricacies of race, gender, and class in travel history."--Keisha N. Blain, coeditor of the No. 1 New York Times bestseller 400 Souls and award-winning author of Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom

"Over the long twentieth century, black women navigated the gendered, sexualized, racialized hierarchies of American railroads, producing something new in American cultural history, a counter-story of Black female railroad history. With meticulous and creative archival research, Thaggert tells the story of Black female fugitive slaves, Black Pullman maids, Black female food vendors, and elite Black women travelers, who challenged the violence and humiliations of race and gendered train spaces and even, in some instances, secured their constitutional right to freedom and mobility."--Mary Helen Washington, author of The Other Blacklist: The African American Literary and Cultural Left of the 1950s

Available Editions

| EDITION | Other Format |

| ISBN | 9780252086595 |

| PRICE | $22.95 (USD) |

| PAGES | 240 |

Links

Featured Reviews

Anita S, Librarian

Anita S, Librarian

Media relevancy note: The television series "The Porter" airing on CBC as of February 2022 should increase interest in this title for readers more interested in the history of Black Americans travelling by rail from the late 1800s to the early 1900s.

The issues surrounding publicly available modes of transportation for Black Americans, particularly during the Reconstruction Era with trains, are vital to understand, but there are gaps in the scholarship of this area of study. There are several excellent titles about the Green Book and motorist guides for African-American travellers particularly in the first half of the twentieth century and that extended past the Civil Rights movement, but they have only been gaining more traction and popularity in the last ten to fifteen years, Many of these texts should be read and understood as well as engaged with far more than the Hollywood motion picture, The Green Book, which glosses over much of the history. It also prioritizes making the white members of the audience feel good about themselves, which is a separate issue. Most of the books that focus on how Black Americans navigated Jim Crows laws and modes of transportation focus on men with the exception of texts about Rosa Parks. Readers should also seek out works about Claudette Colvin as well as the Montgomery Bus Boycott and Freedom Riders to understand the full context of the era, as well as biographies of other significant Civil Rights leaders at the time, such as Fannie Lou Hamer. This book, "Riding Jane Crow," focuses first on how the first class car of trains was a major site of racial antagonisms where Black passengers faced some of the most extreme forms of violence in the efforts of whites to displace them and question their presence.

One of the histories discussed in this text is of the Craft family, particularly Ellen Craft, who produced a slave narrative detailing the escape from slavery in the early 1860s with various modes of transportation including steamboats, carriages, ferry boats, and trains. Ellen had to pass as a white male planter. The author discusses and analyzes the history of racial segregation on the railroad particularly through the examination of lawsuits filed by African American women against railroad companies for discrimination, harassment, and in some cases, violence toward them. The author also discusses the destabilization of racial, gender, and class conventions "both in first-class travel spaces and in the U.S. courtroom in the 1880s." She looks at specific women's cases including Sally Robinson, circa 1883 as well as the views of Anna Julia Cooper and Mary Church Terrell who argued for expanded discussions of railroad spaces--no just compartments but also station platforms, ticket counters, and waiting rooms -- "...all the areas people must encounter in order to travel." Of particular note is the analysis of Terrell's semi-autobiographical short story, "Betsy's Borrowed Baby," about a young woman of colour who travels back from the school she attends in Ohio to the Deep South where her family is from.

One of the cases discussed is that of Harriet Jacobs, whose slave narrative "Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl" was published in 1861. When Harriet became emancipated, she was disturbed to find the discrimination faced by Black travellers on rail travel when trying to escape the South to make it to Philadelphia and then New York. She related that 'colored people' were not allowed in the first-class cars of trains. Colored people were 'allowed' to ride in 'a filthy box, behind white people, at the south, but they were not required to pay for the privilege.'

Other African-American women who encountered these early train experiences included Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Francis Ellen Watkins Harper, Susie King Taylor, and several others. This book is as much an education in the earliest civil rights leaders in Black American history, such as Terrell, as it is a focus on rail travel for Black women beginning in the Reconstruction Era and beyond.

The author emphasizes that African-American womens' travel experiences were very different from the romanticized notions that white male writers often relied upon.

Also discussed is the steamboat as a mode of transport, and the difficulties of navigating those systems for Black women. Scholars argue that railroads had segregation policies that seemed arbitrary in many cases, at least before the 1890s.

Additionally, the author highlights some of the experiences of Black men using rail travel during the era, including Booker T. Washington, which will be of interest to readers.

Detailing everything from platform "policies" to the threats of sexual assault and solicitation as well as racialized violence and hostility that Black women dealt with when travelling by rail, "Riding Jane Crow" is an essential addition to both public and academic libraries not only for its fascinating scholarship on a much-needed gap in the scholarship in this area but also for its illuminating entries on the greater sociological context of these issues.

Riding Jane Crow is in conversation with television shows such as the CBC produced Porter and Amazon’s The Underground Railroad, and books like Kaia Anderson’s Sisters in Arms: A Novel of the Daring Women Who Served During World War II. This academic entry provides entries from legal suits and passages from Pauli Murray, Mary Terrell Church, and Anna Julia Cooper regarding what it was like for a Black woman to ride a train after enslavement.

This book was overly concerned with respectability politics of dress and deportment of (white) ladies and does not provide lengthy analysis of class and colorism: I got the distinct impression that the complaints levied by some of the women was due to their disconnect from “regular” and less monied Colored people, who should countenance the discomfort of the Colored train cars. As that could not be said of them, action was taken to remedy this slight through litigation. To be clear, this was not overtly stated, yet permeated many of the chapters.

All told, this provides an academic companion to the uses of train as travel for Black people and is worth the read if you are interested in historical context for the aforementioned media.

This book was very informative. The anecdote in the introduction provides a captivating entry into learning about something as serious as Jane Crow segregation. I am a frequent train traveler myself, and could not imagine riding under these circumstances. This book does a good job at describing it. I also enjoyed learning more about historic women like Mary Church Terrell, Ida B. Wells, and Pauli Murray. The fact that the book also included photos made it even better.

Charlotte J, Educator

Charlotte J, Educator

After learning about Pauli Murray and the sense of freedom Pauli found riding the rails, I was eager to dive into Riding Jane Crow. Miriam Thaggert expertly ushers the reader through fascinating primary source materials to uncover the forgotten and varied experiences of Black women riding and working on trains in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Like all the best history books, Riding Jane Crow left me wanting to learn more about human experiences I'd never even wondered about before.

Much thanks to NetGalley and the author for an opportunity to read and review the book prior to publication.

Everyone loves a good train story. Not only do they merge the limitless feeling of traveling by locomotive with the very real anxieties that can pervade a closed cabin, but they also challenge our notions of public and private spaces, packed as bodies can become within a train’s walls and a story’s narratives. In the United States, where such communal spaces are otherwise dismally lacking, there are perhaps few junctions of history as collective as the train story, representing a shared mastery over the continent’s vast landscape and the time that would otherwise be required to traverse it. Yet for a history that is so often presented as one of national progress, the actual historical archive of the train story paints a much different picture, and one in which a particular American voice is conspicuously absent—the voice of the American Black woman.

This is the historical contradiction that lies at the heart of Miriam Thaggery’s captivating new book, Riding Jane Crow. In the archive as in the racially-charged space of the train car, Thaggert argues, where Black women appear, they are often present in terms of their displacement or loss of agency. In the opening of the book, the author begins with an account of the Sistahs on the Reading Edge, a Black women’s reading group from Antioch, California, which was forcibly ejected from the Napa Valley Wine Train as recently as 2015. The offense cited at the time was that the women had been too loud. When the train line later posted a statement online, it added the charge that the women had been verbally abusive. And while the train line eventually admitted these claims to be false, the ensuing lawsuit exemplified the displacement that runs as a constant through the history of both Black women and American train travel. It’s a displacement that not only makes the stories of Black women often difficult to locate in the archive of train history but one that makes them that much more important as the truest measure of American freedom and progress.

One of the remarkable things about Riding Jane Crow is the finely-tuned degree to which it engages intersectionality. Much like a body within a train station, the book’s many subjects are tasked with locating themselves using the often-competing identifiers forced upon them—the identifiers, in this case, of race, gender, and class. In an effort to demonstrate these categories’ effects on Black women through time, Thaggert highlights the perspectives of four distinct groups of women riding Jane Crow: Black intellectuals who give written accounts of their own travel experiences; middle-class women of some means who enact their legacies through legal recourse; waiter-carriers who work serving food on the tracks of the Gordonsville, Virginia rail station; and the maids employed by the Pullman Company on their luxury cars, so often circumscribed by the better-documented porters of the Company. By reading each of these Black women through the joint spaces of the train compartment and the archive, “[their] neglected narrative comes into view, showing yet another aspect of African American women and American railroad history.” As Thaggert shows, each of these perspectives fundamentally contributes to the historical train-riding experience in some way, and yet unearthing each woman’s story yields details about that experience that go largely unvoiced.

Appropriately enough, Riding Jane Crow cannot be easily characterized as a text. Insofar as it is a work of intellectual history, it’s also a careful treatment of historical aesthetics. It’s an imaginative book to the extent that it’s a work about the movement of ideas; but highly aware of the ethical nature of its subject matter, it never veers into the world of abstraction, staying grounded in the material reality of its primary sources. Luckily for the reader, this also means that no resource is too obscure or eccentric. Alongside letters and stories, Thaggert collects blueprints, schematics, and advertisements, constructing a door-to-door picture of the course that a train ride may have taken. She compares the celebratory train songs popularized by Black women to the lonesome masculine counterparts so deeply ingrained in the American musical tradition. In a particularly memorable part of the second chapter, the author draws directly from court documents and newspapers, detailing one of Jane Brown’s legal experiences with the Memphis and Charleston Railroad after her violent removal. The sheer breadth of sources surrounds the reader like the instructive placards of a railway station, allowing each historical moment to take on a life of its own as something visual, spatial, and representational so that to read this book is to have a bodied experience.

Miriam Thaggert’s Riding Jane Crow is a must-read for anyone interested in the life of the train in American history, and especially the racial underpinnings that are less frequently the topic of its story. But the book also represents the undertaking of an astonishing scholar, furnishing hundreds of primary sources by which the reader can and should continue to educate themselves on the topic. While Thaggert expertly toes the line between her voice and those that are not her own, she takes care to present those voices with grace, genuine curiosity, and above all, historical import.

Review by Lake Markhan