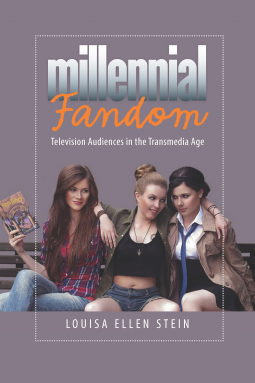

Millenial Fandom

Television Audiences in the Transmedia Age

by Louisa Ellen Stein

This title was previously available on NetGalley and is now archived.

Send NetGalley books directly to your Kindle or Kindle app

1

To read on a Kindle or Kindle app, please add kindle@netgalley.com as an approved email address to receive files in your Amazon account. Click here for step-by-step instructions.

2

Also find your Kindle email address within your Amazon account, and enter it here.

Pub Date Aug 15 2015 | Archive Date Dec 01 2015

University of Iowa Press | University Of Iowa Press

Description

These conflicting narratives of entrepreneurial creativity and digital immorality operate to quell the growing threat represented by millennials' media agency. With fan activities becoming ever more visible on social media platforms including YouTube, Facebook, LiveJournal, Twitter, Polyvore, and Tumblr, the fan has become the avatar of our digital hopes and fears.

In an ambitious study encompassing a wide range of media texts, including popular television series like Kyle XY, Glee, Gossip Girl, Veronica Mars, and Pretty Little Liars and online works like The Lizzie Bennet Diaries, as well as fan texts from blog posts and tweets to remix videos, YouTube posts, and image-sharing streams, author Louisa Ellen Stein traces the circulation of the contradictory tropes of millennial hope and millennial noir. Looking at what millennials do with digital technology demonstrates the molding impact of commercial representations, and at the same time reveals how millennials are undermining, negotiating, and changing those narratives.

This generation—and the fans it represents—is actively transforming the media landscape into a dynamic, culturally transgressive space of collective authorship. Offering a rich and complex vision of the relationship between fandom and millennial culture, Millennial Fandom will interest fans, millennials, students, and scholars of contemporary media culture alike.

Advance Praise

“A distinctive and original take on participatory culture, Millennial Fandom is an impressive study of the cultural and gendered ramifications of social media engagement. It will become essential reading for anyone hoping to understand millennials and the impact of their attitudes toward gender and media use on contemporary culture.”—Jennifer Gillan, author, Television Brandcasting

“Stein’s work traverses the networked contours of a rapidly fragmenting media culture to represent fandom in positive, political, and productive ways. She spotlights a new generation and offers an important window on contemporary developments in transmedia storytelling and net-based fan cultures.” —Mark Duffett, author, Understanding Fandom

Available Editions

| EDITION | Paperback |

| ISBN | 9781609383558 |

| PRICE | $24.00 (USD) |

Links

Average rating from 14 members

Featured Reviews

Reviewer 258704

Reviewer 258704

Very interesting study of the way media effects the current generation.

Victoria I, Media/Journalist

Victoria I, Media/Journalist

Millennial Fandom: Television Audiences in the Transmedia Age by Louisa Ellen Stein is an academic look at the power of fandom and its effects on the Millennial culture. While this may immediately sound like the next book you skip, hear me out; Stein is one of us. A major "Gleek," Stein found herself enraptured with the show Glee as well as various other TV shows. In this fandom, she began to branch out and explore what it means to be a fan, the power of fandom and just what importance the Millennial generations have on marketing, social interaction and the next wave of media.

Millennial Fandom takes a look at television shows such as Kyle XY, Pretty Little Liars, Revenge and Veronica Mars to show what type of media we are taking in as a grouping, as well as how our viewing habits have changed the culture around us. For example, fans protested when certain stations refused to show a gay kiss from Glee. It also shows how we have come to expect social interaction from our media, such as the now defunct Kyle XY website and Twitter. Stein even spends a great deal of the book talking about Misha Collins becoming a Twitter celebrity after his time on Supernatural and how he managed to turn that into a major network for social change. Stein even attended Leaky Con and wrote about that experience.

Millennial Fandom: Television Audiences in the Transmedia Age is one of those books that can hide out on your shelf and appear to be academic literature, but in equal measure acts as an interesting read on media and fan culture.

Millennial Fandom: Television Audiences in the Transmedia Age is available from The University of Iowa Press August 15, 2015. Look for it on Amazon; on Powell's

Rebecca T, Educator

Rebecca T, Educator

Louisa Ellen Stein, Millennial Fandom: Television Audiences in the Transmedia Age: Stein doesn’t really define “millennial” here; it’s basically “the current wave of fandom,” focused on now-current or recently-ended shows directed at young people; media (fanvids and gifsets), and sites (Tumblr). Stein argues that these shows and their fandoms represent millennial hope (Glee) and millennial noir (Pretty Little Liars), and also that the shows participate in the gendered construction of fans and millennials as more consumer-friendly and mainstream than previous understandings of media fans. Along with PLL, she argues that Revenge and Veronica Mars offer the “merger of the infamous femme fatale with the private investigator into a single threatening, empowered, yet sympathetic female lead” who uses technology to fight bad guys and sometimes to be the bad guy herself. The audiences for these shows then “emulate the power of these characters in their own digital networks and digital authorship.” Even more audience-integrated productions like The Lizzie Bennet Diaries and the Misha Collins fandom work hard to create a sense of shared community but also a recognition of “professional” authorship. The individual in this conception develops as an individual by figuring out and embracing her role in a broader community: this, Stein says, is the theme of discourses designed to construct or intended to reflect “millennials”—in many Glee plots, for example, return to the collective is the big finish for many individual characters’ conflicts, resolving seemingly irreconcilable differences by inclusion in the whole. (See also: Community.)

Millennial noir shows like PLL are less chipper—they“depict millennials as morally ambiguous, as adult before their time, and as digital pirates with no respect for institutions—unless they themselves own those institutions. They show millennials as simultaneously perpetrators and victims of modern cultures’ excesses, at once digital terrorizers and digital captives.” They focus on “technologically empowered young women whose desire, curiosity, and quest for control drive the narrative.” Which leads naturally to questions about female fans; Stein argues that millennial noir celebrates gender ambiguity rather than elevating male fans over female fans. I found this a bit in tension with her idea that the heroines of these shows are “filles fatales”—young women who have noir signifiers but are the protagonists rather than the objects of the narrative; that doesn’t seem like gender ambiguity to me. She also contends that these series “also depict sympathetically ambiguous male characters, antiheroes trapped within the confies of societal restrictions of masculinity,” who “cross gender lines as they serve as the female heroines’ muse, inspiration, supporter, victim, or duplicitous homme fatale.” I’m not sure I recognize Duncan Kane or Logan Echolls in there, though a fair number of the men on PLL could fit somewhere in there.

I liked her point about the voiceover as noir technique, providing access to female characters’ interior lives and thus turning characters who might be femmes fatales into the heroines and main points of identification (Veronica Mars, Gossip Girl and Revenge). Unlike classic noir, in which the femme fatale is the mystery to be solved, in millennial noir it’s the victimization of the fille fatale that’s the problem in need of a solution—“a compounded problem of gender and generation.” Young women use technology to find out things and get power “within a society that has rendered them powerless.”

The other thing that’s unlike classic noir, Stein says, is the role of community—what I would call found or chosen family. Nolan Ross, Wallace Fenell, Eli Navarro, the Liars—these are participants in networks formed to fight larger problems, which Stein says replicates “the feminist recognition of the political in the personal and vice versa.” I’m not sure how this really differs from classic soap opera, because I’m not a huge soap opera fan, but I see continuity with Melrose Place and the like, and not just because of Mrs. Marin. But it’s true that VM at least pays more attention to class, though it’s hard to say that PLL does; and Revenge does so only in the “follies of the rich” way. Interestingly, the community also appears in the antagonists: A and Gossip Girl are roles, not specific people—creating a dangerous collective opposed to a powerful and protective collective.

These unruly heroines, Stein argues, look a lot like the “digitally empowered, (supposedly) excessively obsessed fangirl.” No longer marginal or parodic, these fangirl types are now the core characters. (Again, not so sure about PLL here, but I’ll buy that for VM and Revenge. If Charlie Bradbury’s sad fate is the last gasp of a dying era, I’ll be happy.) Because these series focus on their active filles fatales, they also reach out to their audiences in ways that invite fans to participate.

But this encouragement, of course, is not of transgression generally or for its own sake, but rather it’s part of a strategy of “engaging” and coopting fans into a commercial framework. Stein discusses various transmedia promotions that have done this, like a Second Life Gossip Girl environment and tweeting with actors while shows go on. Fans, of course, don’t remain nicely contained, and so Stein reviews some fanworks and picks examples that generally support her argument that fans go further in making the noir “more explicit, more nostalgic, or more politicized. A signifiant number of millennial noir fan fiction stories use first-person hard-boiled narration to offer a different vision of a character’s perspective or to create compelling, complex versions of characters who may not be as fleshed out in the original source text.” I wasn’t deep into the fanwork side of these shows, though I watched them (I bowed out of GG after S2), so I can’t tell if her examples are representative.

I thought this bit was particularly well said: “Millennial fan works may transform via critique and vice versa, but even critical works … emerge out of a respect for the potential of elements of the source text, if not its official execution.”

The last part of the book focuses directly on fandom, specifically in its participation in a change from an idea of the author as “privileged individual” to a more “decentered, creative collective engaged in a continual process of transformation.” This collective, Stein argues, tries to unite performance of high emotion (“feels”) and skill, moving fandom from margin to mainstream and from taboo to common denominator.

Stein discusses Misha Collins’ fandom interventions and suggests that the digital environment has exposed the processes of production both for fans and for professionals: chapter by chapter fanwork posts (feedback please!) are matched by tweets from verified accounts about how filming is going. The labor on both sides is visible and now has a semi-permanent record. This “double visibility” provides ways for fans and official producers to connect, interact, and overlap.

While this can be disconcerting for established authors/auteurs, it offers opportunities for new entrants like Misha Collins “to inhabit new modes of celebrity that embrace the commonalities between producer and audience.” As a minor celebrity, Collins can occupy a liminal position embracing both his relative lack of power within the professional world and relative excess of power within the fanworld. Collins “has developed his star persona by aggressively performing this middle place of transmedia stardom”—and “performing” is an important word here because it is so clearly a performance, though it only works as a sincere performance. This kind of contradiction is central to these new forms of interaction: Collins and his Random Acts charity emphasize “themes of shared collective good and the power of the digital collective while also selfreflxively highlighting power imbalances in the hierarchical structures of web culture and of celebrity–fan relationships.”

As a SPN fan, I also really liked Stein’s discussion of Castiel the character: Spock-like, he “dramatizes themes of power, desire, and marginality key to the fan experience. His alienness renders him both powerful and disempowered. Ths duality in turn resonates with the contradictions of the millennial fan position: fans are powerful in the realm of fan-authored digital media but wield little control over the official text that is the object of their fandom.” And because this is SPN, the narrative has to punish him for his liminality/sympathy to fandom: Stein reads The French Mistake as, in part, a satire/rejection of Collins and his fans:

It depicts him as a pampered actor who wears a sweater jacket and bursts into uncontrollable tears while pleading for his life. In the world of Supernatural, where machismo and the strategic release of male suffering (in the fan-favored form of “one perfect tear”) are core values, fictional Collins’s excessive emotion is taboo. In addition, fictional Collins’s in-episode tweets suggest that he is too close in kind to fans; he uses fan terms like “J2” and mistakes for real intimacy an imaginary relationship with the series’ stars.

Plus he’s violently killed off, as is departed creator Kripke—the abandoning father and the wayward son, Stein argues, are both punished by the narrative. But within this punishment, reward lurks: the episode also made him more visible as a Twitter author/celebrity, and his follower count shot up “remarkably” during the episode. Though the manuscript seems to have been finalized before the end of S10 (though after Fan Fiction), Charlie’s fate is perfectly consistent with Stein’s reading.

Stein also considers “feels culture” more broadly, exemplified by the vlogs of The Lizzie Bennet Diaries. She argues that feels culture “thrives on the public celebration of emotion previously considered the realm of the private.” Emotions “build a sense of an intimate collective, one that is bound together precisely by the processes of shared emotional authorship.” Here the book would have benefited a lot from some historicization—this doesn’t seem all that different from other kinds of public culture; the emotions acceptable to express, for men and women both, have changed in the West a lot in the past few centuries. I agree this may well be a local change, but it is local. I also wonder to what extent it has its counterparts in, say, the incoherent rage of Fox News and Donald Trump—look at the nearly LOLspeak dissent Justice Scalia just wrote in the marriage equality case and you’ll see feels culture right there.

In fandom, though, emotion is a spur to transformative creativity, and “performances of shared emotion define fan authorship communities.” Stein contends that millennial fandom culture combines “an aesthetics of intimate emotion—the sense that we are accessing an author’s immediate and personal emotional response to media culture—with an aesthetics of high performativity, calling attention to mediation and to the labor of the author.” This certainly feels accurate to me, but it seems to me that it’s also true, though perhaps in different ways, of zine fandom, where the less-professional presentation contributed to the sense of personal touch. Literally: at least in many cases, fans assembled zines by hand; another fan held the stapler, or at a minimum stuffed the envelope, that brought you the latest Kirk/Spock. What Stein identifies is the way this plays out with digital fandoms, which is very interesting, but does have continuities with the past that are not her concern in this book.

Readers who liked this book also liked:

Alfred L. Martin, Jr.

Arts & Photography, Multicultural Interest, Nonfiction (Adult)

Nigel Henbest; Simon Brew; Sarah Tomley; Ken Okona-Mensah; Tom Parfitt; Trevor Davies; Chas Newkey-Burden

Entertainment & Pop Culture, Humor & Satire, Nonfiction (Adult)