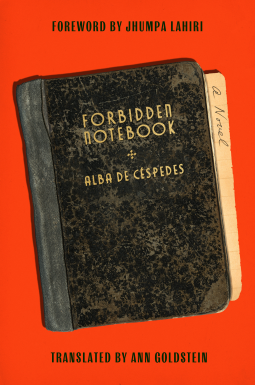

Forbidden Notebook

A Novel

by Alba de Céspedes

This title was previously available on NetGalley and is now archived.

Send NetGalley books directly to your Kindle or Kindle app

1

To read on a Kindle or Kindle app, please add kindle@netgalley.com as an approved email address to receive files in your Amazon account. Click here for step-by-step instructions.

2

Also find your Kindle email address within your Amazon account, and enter it here.

Pub Date Jan 17 2023 | Archive Date Jan 01 2023

Astra Publishing House | Astra House

Talking about this book? Use #ForbiddenNotebook #NetGalley. More hashtag tips!

Description

“Powerful.” —The New Yorker

“Brilliant.” —The Wall Street Journal

"Astounding." —NPR

“Forceful, clear and morally engaged.” —The Washington Post

“Subversive.” —The New York Times Book Review

"An exquisite, tormented howl." —The Financial Times

"Quick, propulsive, and addictive." —Los Angeles Review of Books

“Gripping.” —Minneapolis Star Tribune

“A remarkable story.” —Publisher’s Weekly (starred review)

“Wrenching, sardonic.” —Kirkus (starred review)

“As relevant today as it was in postwar Italy." —Shelf Awareness (starred review)

With a foreword by Jhumpa Lahiri, Forbidden Notebook is a classic domestic novel by the Italian-Cuban feminist writer Alba de Céspedes, whose work inspired contemporary writers like Elena Ferrante.

In this modern translation by acclaimed Elena Ferrante translator Ann Goldstein, Forbidden Notebook centers the inner life of a dissatisfied housewife living in postwar Rome.

Valeria Cossati never suspected how unhappy she had become with the shabby gentility of her bourgeois life—until she begins to jot down her thoughts and feelings in a little black book she keeps hidden in a closet. This new secret activity leads her to scrutinize herself and her life more closely, and she soon realizes that her individuality is being stifled by her devotion and sense of duty toward her husband, daughter, and son. As the conflicts between parents and children, husband and wife, and friends and lovers intensify, what goes on behind the Cossatis’ facade of middle-class respectability gradually comes to light, tearing the family’s fragile fabric apart.

An exquisitely crafted portrayal of domestic life, Forbidden Notebook recognizes the universality of human aspirations.

Available Editions

| EDITION | Other Format |

| ISBN | 9781662601392 |

| PRICE | $26.00 (USD) |

| PAGES | 288 |

Featured Reviews

Reviewer 205760

Reviewer 205760

The Forbidden Notebook is a novel that has the quality of something meticulously embroidered: its writing so intentional, its insights so particular, that what you get in the end is something that, like embroidery, feels intricate and painstakingly made--also, so very impressive. The premise of The Forbidden Notebook is a seemingly straightforward one, and indeed one that has long been mined for narrative interest: a housewife becomes increasingly aware of her discontent with her life. And yet the way de Céspedes takes this premise and makes it her own is just remarkable; the narrative that she gives us here is a testament to how, in the right author's hands, a premise like this can provide the grounds for fresh, invigorating, and really profound storytelling.

What is most striking to me about this novel is its precision, the nuance and care with which it presents the interiority of its protagonist, Valeria. It's such a psychologically rich novel, written with a keen eye for the ways in which we are fallible, liable to contradict ourselves, to elide uncomfortable truths. We get to see this unfold through Valeria's entries, which she writes in her "forbidden notebook": entries where she is especially attuned to the dynamics of gender, labour, and money. The family is a microcosm for these issues, and the dynamics of Valeria's family in particular are no exception. There is her fraught, though deeply moving relationship with her daughter, who challenges what Valeria takes for granted about women's roles in romantic and professional spheres. There is Valeria's son, a kind of foil to her daughter, who is more embedded in what's considered "traditional," though this becomes complicated as the novel goes on. And of course there is Valeria's relationship to her husband: its romantic and sexual elements, its economic underpinnings (Valeria works to supplement her husband's income), and, by extension, the division of labour that is attendant to it. On top of all of this, which I thought was fascinating, I loved, too, both Valeria and de Céspedes's attention to spaces and the many ways in which they contour or bring into distinction the characters' identities and roles: the bedroom, the kitchen, the office, the streets.

More broadly, The Forbidden Notebook is a very layered novel in the way that Valeria tries to understand herself through writing while we also try to understand her through that very writing. Her investment in her own project--however unclear that project is to her sometimes--is also our investment in that same project. Those two things--Valeria's reading of herself, and our reading of her--also enrich the story and add to its already complex dynamics. On the one hand you want to give credence to Valeria's understanding of herself, but on the other you become increasingly attuned to the fact--as Valeria herself does, sometimes--that she is often not truthful to herself, unwilling to put into writing what she really thinks or feels about something. What we get, then, is a tension that persists throughout the novel (one that Jhumpa Lahiri nicely points out in her foreword): a tension between the diary as this way of gaining deep, unfettered access to Valeria's psychology, and the diary as a kind of tool to avoid or gloss over certain truths by way of the editorializing or narrativizing that writing allows.

Incisive, lucid, searing, The Forbidden Notebook is the kind of novel that, to me, feels like a miniature: scaled down but at the same time speaking for something bigger than itself. It's a stunning character study, a feat of realist writing that's a testament to how utterly absorbing it can be to become invested in the small dramas of someone's everyday life.

(Thank you to Astra House for providing me with an eARC of this via NetGalley!)

Forbidden Notebook – Alba de Cespedes (translated from Italian by Ann Goldstein)

Another upcoming release, this one is out on 17th January 2023 through @astrahouse – thanks to them and @netgalley for this copy!

A 1952 publication from Italy, “The Forbidden Notebook” tells the story of Valeria Cossati, a woman unaware of how unhappy she has become with her life. She has a husband, two children, all the trappings of social acceptability, which is fine for her, until she starts writing her thoughts and feelings in a little black book she keeps hidden in a closet. At first she is almost traumatised by the illicitness:

“I was wrong to buy this notebook, very wrong. But it’s too late now for regrets, the damage is done.”

Soon, however, she begins to scrutinize herself and her life more closely, and she soon realizes that her individuality is being stifled by her devotion and sense of duty toward her husband, daughter, and son, as well as the expectations of a patriarchal society. At first, she seems unaware, making comments that the reader sees clearly, for example:

“I thought maybe I’m starting to get irritable, cranky, like all women— it’s said— when they pass forty.”

Quickly, however, internal family conflicts and revelations tear at the fabric of her family life, forcing her to take stock of everything she has and reevaluate what she finds important, and .

“Facing these pages I’m afraid: all my feelings, thus dissected, rot, become poison, and I’m aware of becoming the criminal the more I try to be the judge.”

An interesting, psychologically precise description of a woman finding a room of her own and both the joys and new challenges that come with it. It’s well-written, full of complex characters, I’m very happy to recommend this one if you’re a fan of Elena Ferrante or Doris Lessing – it feels like a good choice for republication.

Does this sound like something in your wheelhouse?

An Italian housewife keeps a diary on the sly in a black notebook.

In her entries she details her fear of someone finding her illicit writings and discovering her secrets.

Writing gives her an opportunity to express her hidden thoughts and opinions. She tries to juggle her family, her responsibilities, and her hidden romance on the side.

I could, relate to the main character because as one who writes in a journal, I don’t want anyone prying into my thoughts.

I felt sad for her because changes in her family causes her to have to give up some of her dreams.

Kelsey G, Reviewer

Kelsey G, Reviewer

I really appreciated how modern and timely this novel feels, even though it was written in the early 50s. The tension between mothers and daughters, wives and husbands, the identity of mothers as individuals, women who work both in the home and outside of the home, class and the struggle to move up in the world... this all feels so relevant to daily life in the 21st century. Maybe the only way I remembered it was written 70 years ago was that the legacy of WWII in Italy was still very strong here. The post-war years in Europe were very different than in the U.S., so I appreciated that insight.

Highly recommend this insightful, honest look at identity and womanhood, that remains just as relevant now as I'm sure it did on its original publication.

Writing leads to an examined life....

The shiny black of the notebook first attracted Valeria, then the word 'Forbidden' completely hooked her in. Thus began her hidden journey into self awareness and awareness of what is around, what was around and what is to come.

Through the notebook Valeria becomes. She examines her life, her past, her family and her future. She also comes to reluctantly admire her daughter who she has brought up bound by the rules her own mother taught her and who challenges these rules all the time, thus making Valeria take a deep look at the rules herself.

Through Valeria, Cespedes examines old values against new values. Old generations against the young generations. Families that include old values, new values, older people, younger people and the ones that bridge them understanding both and being understood by neither side.

An ARC kindly provided by publishers via Netgalley

Valeria buys a notebook illegally (on Sunday when the seller should have sold only tobacco). But after buying it, she still considers her notebook forbidden because she thinks her family wouldn’t approve of her writing the diary. The very first sentences in the notebook (and also the first sentences of this novel) tell us she considers this writing in a diary as something forbidden.

"I was wrong to buy this notebook, very wrong. But it’s too late now for regrets, the damage is done."

Keeping a diary causes Valeria to analyze daily occurrences more closely. She notices everyday events that previously went unnoticed. Before starting her diary, these occurrences slipped her mind entirely. Writing in her diary becomes a routine, a vital practice for Valeria. The diary serves as her sanctuary, a place where she feels safe. (She doesn’t have a room of her own, or even a drawer).

Valeria, at first, wanted to write a serene story of her family. In the end, however, the story does not turn out serene at all. As she continues to write in her diary, she uncovers more and more things that bother her. She realizes that no one helps her with the household chores, and everyone expects her to do them. She is always tired and realizes that her family does not understand her.

I can’t help but notice that this is, in a way, such a timeless story about finding your own voice, about a woman who wants to be treated as an individual and not just a part of the family. Not just a mother or a housewife (the one who cooks, cleans, or irons clothes).

Juli R, Reviewer

Juli R, Reviewer

Sometimes you start a book without knowing it's going to have a major impact. For me, Forbidden Notebook was one of those books which, as the pages read increased, began to worm its way into my brain and probably make longlasting changes. Thanks to Astra Publishing House and NetGalley for providing me with a copy of this book in exchange for an honest review. My sincere apologies for the delay in reviewing!

'all women hide a black notebook, a forbidden diary. And they all have to destroy it." In Forbidden Notebook I found a painfully sharp and heartbreakingly tender depiction of something I have been thinking about for a while, which is the shifting expectations of what a woman should do and be, and how this impacts various generations of women. Looking at my own family, both my grandmothers were stay-at-home mothers, who were nonetheless always involved socially in various causes. My mother found herself in a different position, with new freedoms and opportunities, yet also still bound by previous expectations. I myself perhaps do not feel those old expectations as strongly, but I do see their impact and how they continue to clash with the different world we find ourselves in. Through the first-person narration in Forbidden Notebook, Alba de Céspedes develops the awareness of this, and the unbearable weight of finding yourself caught between two worlds, in Valeria and it is heartbreaking to read. It is also important, however, to get an insight into this shift in a book from the '50s and to recognise how much of its elements still ring true. Alba de Céspedes manages to create a profile of a woman who is so restricted by her upbringing and her society, who believes much of what she has been taught about women and their abilities, and who yet discovers a wellspring of thought and ability in herself.

One day, Valeria buys a notebook, even though its forbidden, and on the 26th of November, 1950, begins writing. Initially she is not sure why she is writing, or why she even bought the notebook. Valeria keeps the notebook hidden from her husband, Michele, and their two grown-up children, Riccardo and Mirella. As she begins tracking her thoughts and the things that happen, a consciousness begins to develop in Valeria, a creeping knowledge that she is not fully happy, not, perhaps, fully alive. While she loves her family, she becomes aware of how trapped she is in her life, caring for them while also working in an office to bring in more money. In her notebook, she tracks Riccardo's dissatisfaction with their family's poverty and its effect on him, Mirella's struggle with traditional expectations of women, and Michele's own quiet unhappiness. As these issues take up her life, Valeria tries to carve out a space for herself, but how can she be free of the person she has become? Forbidden Notebook is a fascinating depiction of restrained womanhood, of the burdens placed on women and the burdens they willingly carry. It is also a stunning depiction of interiority, of a person's sense of self developing across the pages. Valeria frequently holds opinions I could not agree with less, and yet she is crafted in such a way that I fully understand how she got there. Especially her relationship with her daughter, Mirella, and the tension between these two different ways of being a woman was fascinating to read. I also found Riccardo's dissatisfaction with his life, and how he lashes out as a response, really intriguing considering the current "crisis of masculinity" we are seeing. Turns out, not so current, but rather a decade-long thing.

I had never heard of Alba de Céspedes before and now I am a dedicated fan. She was a Cuban-Italian writer of fiction, who also worked as a journalist. In 1935, and again in 1943, she was even jailed in Italy for her anti-fascist activities. First published as Quaderno proibito in 1952, this book speaks directly to that after-war period and I think you can see a lot of criticism and consideration of the effects of war in this book. As a working woman herself, I also am intrigued by how she explores the balancing act required of Valeria, who on the one hand needs to work to assist the family and yet, on the other, needs to consistently deny she is gaining anything else from it. The way the drudgery of the home is explored, as well as the oppression of poverty, the loss of privilege and changing social rules, it all speaks to a very insightful author. As I mentioned in the first paragraph, Forbidden Notebook spoke directly to thoughts I had been having and I found myself aching for the women of the past few generations, who saw the change in women's rights and yet also, perhaps, saw it pass them by. I think for any reader interested in female characters with subjectivity, interiority, and the desire to judge for themselves what is true in their lives, Forbidden Notebook is a must read.

Forbidden Notebook blew me away to an extent I had not expected. This novel made me challenge the ways I think of previous generations of women in my own family, the struggles they experienced which feed into my freedom, but also made me treasure that I have a room of my own to write in.

Readers who liked this book also liked:

Patti Callahan Henry

General Fiction (Adult), Historical Fiction, Women's Fiction

Jodi Picoult; Jennifer Finney Boylan

General Fiction (Adult), Literary Fiction, Women's Fiction

Laura Shepherd-Robinson

General Fiction (Adult), Historical Fiction, Mystery & Thrillers